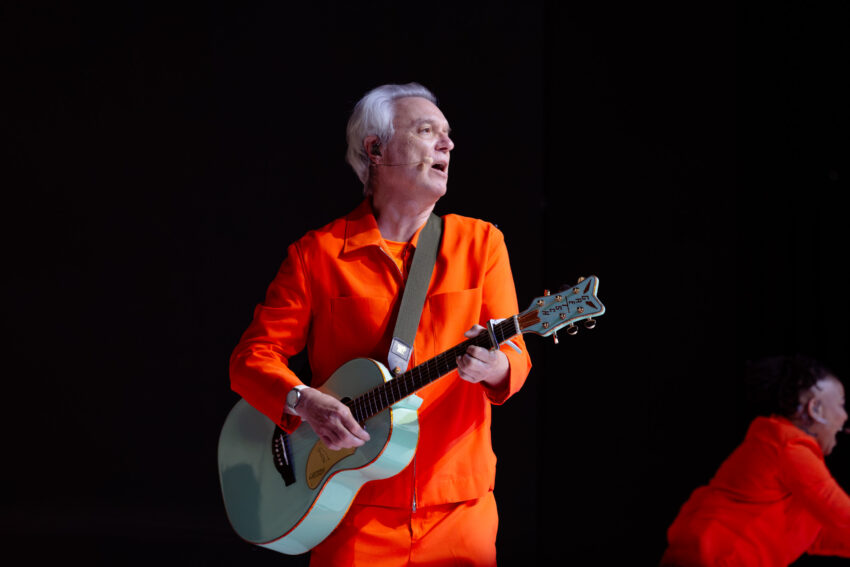

David Byrne

Sidney Myer Music Bowl

January 23, 2026

David Byrne walked onto the Sidney Myer Music Bowl stage with effortless confidence, flashing a bright orange jumpsuit that matched his perfectly choreographed band. Within moments, the entire ensemble appeared to float across a vast LED moon, suspended in space and set upon the lunar surface. It established the tone for the night: surreal, playful, and unmistakably Byrne.

From the outset, he shaped the show around connection. Before launching into And She Was, he joked, “I keep being reminded I shouldn’t be laughing at my own jokes,” fully aware he would continue doing exactly that. The crowd adored him for it. Not a single person expressed anything but joy and admiration — Byrne’s gravitational pull was undeniable.

During T Shirt, the screens fired off designs like “Make America Gay Again” and “Melbourne Kicks Ass,” each earning louder cheers than the last. Byrne absorbed it all with the grin of a cheerful veteran performer who still seems genuinely delighted by the world’s oddities.

The emotional high point arrived with This Must Be the Place (Naive Melody). When he sang “heart stops,” the entire Bowl erupted out of a moment of breath‑held silence — a sudden, overwhelming release of feeling. Byrne let the energy settle before offering what felt like the thesis of the night: “Right now, love and kindness are the most punk thing you can do.” Moments later, before Love Is Here, he reminded everyone that love and kindness are a form of resistance.

Between songs, Byrne’s stories unfolded like sharp, affectionate observations. He spoke about Italians singing to their neighbours during lockdowns, introduced his band by floating their names across a star‑filled screen during Independence Day, and laughed off a rogue scream of applause. He teased the audience about judging by appearances, quizzing them on who among them had astrophysics degrees — and who had been home schooled. He recounted being mistaken for Norman Bates at the Jazz Festival, insisting that appearances reveal very little. And before My Apartment Is My Friend, he described witnessing someone throw potatoes at someone else, confessing, “No one seems to be handling this the same way as me,” as he introduced his apartment on the backdrop as his “safe haven.”

A tribute to Arthur Russell paved the way for the eruption for Psycho Killer, the Bowl transforming into a choir as thousands sang back in harmony. Before the encore opener Everybody’s Coming to My House, Byrne reflected, “Despite all that stuff, people really like being with other people.” Under a perfect Melbourne summer night, the truth of that line felt amplified.

The final songs carried a striking irony. Everybody’s Coming to My House — a song that once played with the tension between welcome and unease — suddenly felt open armed and communal, thousands of voices rising together under the summer sky. Moments later, Burning Down the House turned the Bowl into a jubilant frenzy, its chaos transformed into pure celebration. Byrne remains avant garde, uplifting, endearing, cheerful, funky, and endlessly inventive. A performer who brings people together not through nostalgia, but through sheer creative force.

If love and kindness are a form of resistance, Byrne offered Melbourne something brighter and more vital than rebellion: a reminder that joy can be its own kind of revolution.

Words and images by Joshua Braybrook